Paper is an ancient material that has been produced and used for over three thousand years, serving as the vehicle for transmitting knowledge and enabling the universalization of culture.

Its availability for use is as immediate as its integrity and preservation are precarious. Its versatility, which makes it so ubiquitous and abundant in everyday life, has also relegated it to the waste heap of the most ephemeral utility.

In the artistic realm, it was not until the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century—with the introduction of collage and décollage techniques—that paper vigorously entered art history as an expressive medium. Until then, its role as a plastic art form had been marginal.

The choice of paper is not merely a procedural matter. To focus on this humble material, always excluded from the rank of «noble» materials in the fine arts, is to rescue it from its endemic undervaluation as an artistic medium and incorporate it into the expressive resources of painting—ultimately, into the realm of art itself. The debate questioning boundaries is neither new to this discipline nor to contemporary art, where genres, moreover, are so easily blurred.

Exploring Materials, Exploring Meaning

Born & Rised

Creating from [2016]

I am a visual artist, painter and sculptor based between Barcelona and Andorra, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Barcelona.

[ Adolf Fontbona

visual artist, painter and sculptor]

From painting to sculpture, installations and film — each project reveals a different perspective of my creative universe.

UNPAINTED PAINTING

The creative process raises questions such as whether the material is truly chosen by the artist or if it chooses the author. Whether the approach to it is innate or conditioned. The very role of the creator—if they are in fact a kind of «medium» who does not fully control the entire creation process—and to what extent the author, as a social subject influenced by everything surrounding them, incorporates the fortuitous events that occur during the creative act.

The material is not only shaped by the author’s own sensibility but also conditions their technique. A procedure must be invented for each material, as it also demands a specific shaping based on what is colloquially referred to as the material «speaking.»

Thus, creative capacity does not emanate solely from the celebrated and intangible inspiration of the author, which is so fiercely hidden within them that they must simply draw out what is inside, as the common place often claims. Rather, the creative process, as a journey of self-discovery, is also social.

Yet beyond illustrating a specific conceptual stance by reclaiming the marginal through a poor and humble material born of recycling—more or less consciously, if one wishes to connect it to Arte Povera—it is above all a choice related to the most intimate, personal, and intuitive aspect: choosing that communicative vehicle which ultimately best identifies the author in the way they want to say things.

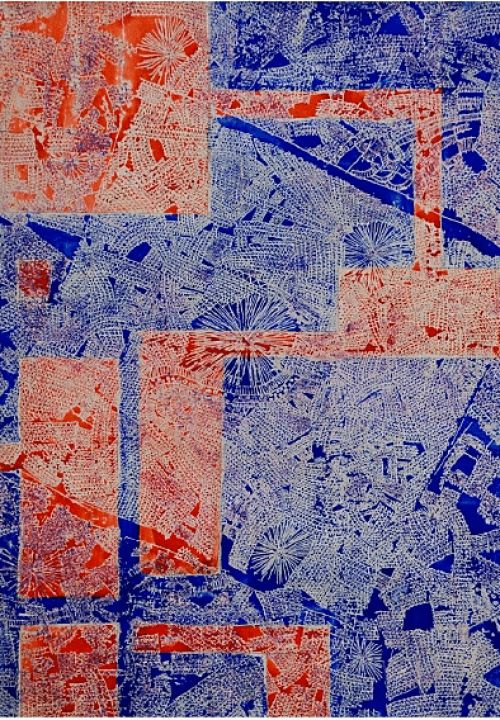

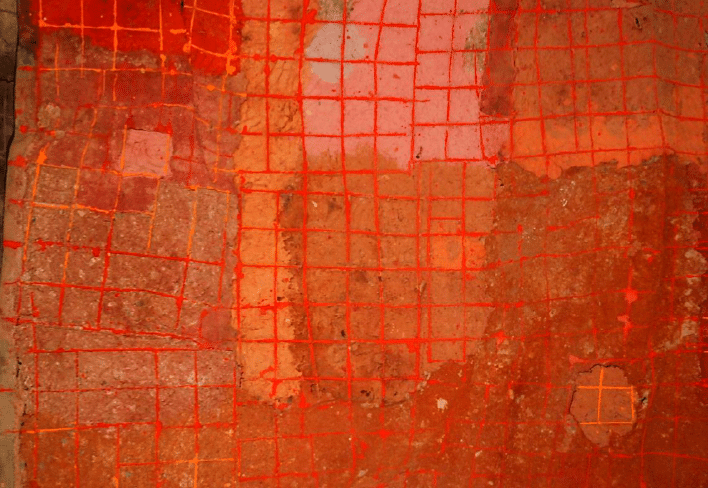

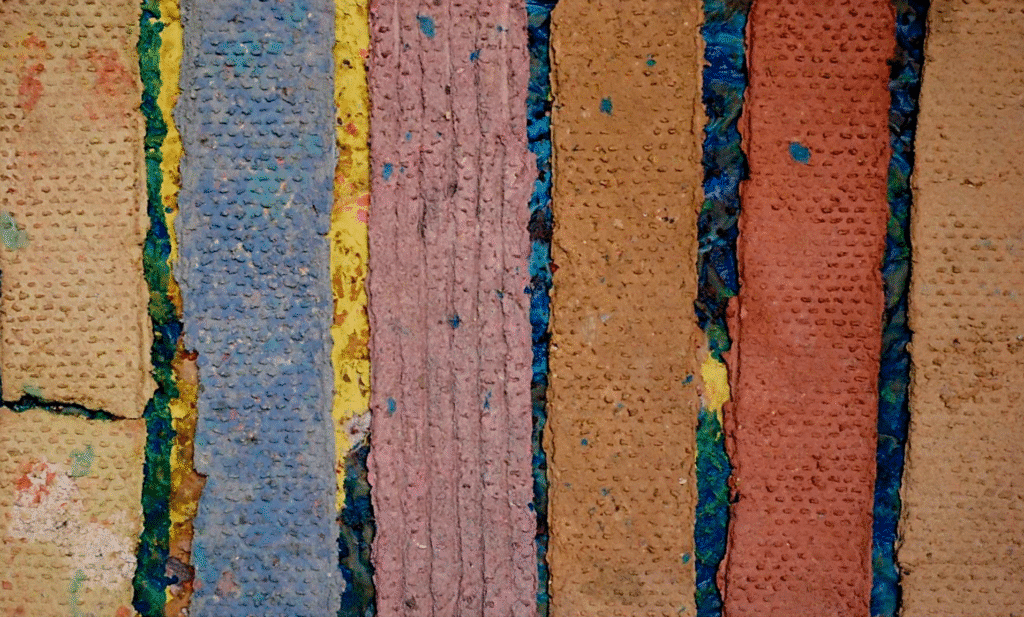

The compositional solutions employed in this sense are diverse, although generally dominated by a resolved geometric routine, either through polychrome grids that give the piece a more pictorial vocation, or through vertical and/or diagonal strips that confer a more graphic character. From a formal viewpoint, these works present themselves as abstract landscapes, stripped of any realistic reference or recognizable motif, avoiding any visual interference and underscoring the tactile emphasis of the paper.

This geometric framework, however, remains ultimately imperfect—more sketched, if you will, than finished. In both cases, the final result is that the structural rigor and severe constructive order of the composition, betrayed in its quest for perfect order, ends up distorted by the textural power of the paper, which often emerges irregular and frayed, aspiring to a timid three-dimensionality. The plastic dichotomy between matter and composition creates a perceptual and formal conflict from which a dialogue of controversy is built.

Adopting the discipline of a framework, in this case an orthogonal grid, is ultimately adopting the most rational and primordial way of organizing a space, whether plastic, as in this case, or physical, like that of a city. This kind of structure is based on the principle of contraposition between two antithetical elements: the vertical crossed with the horizontal. Like the negative of a positive, the contrasted contradiction between opposites reveals the mutual reality of both, which, at the end of this struggle, become a third element of consensus and balance—in this case, the square.

Color adds the other ingredient that intervenes in perception. The polychromy, alternating between often highly saturated cold and warm tones, ultimately gives the work a fragmentary and dynamic character that seems to want to transcend the physicality of the paper rather than emphasize it.

The paper used in these works is that which has already achieved the status of waste, or refuse, because it has been consumed and discarded from its primary use. The patina of the used, exuded by this true «ragpicker’s paper,» also confers the added value of lived matter, still alive despite everything. Once collected (and accumulated), the subsequent process involves mixing it with water to obtain a new state in the form of pulp.

The especially ductile manipulability offered by paper worked wet allows for expressive possibilities not achieved with other procedures, particularly in terms of material and tactile accents. The surfaces of torn, tortured, or wounded texture achieved in these works seem to become an echo of the bloody process of destruction that has allowed the paper to attain this second, artistic life.

The result is that, in the end, these works impudently exhibit a deliberate physicality, endowed with a certain tone of almost prudish warmth and an archaeological vocation, which does not hide the will to transcend it.